The Real “Van”

As the global capitalist system tumbled over a cliff in the late 1920s, French teenager Jean van Heijenoort took the first steps toward a two-decade career as a professional revolutionary, the crucial part of it at Leon Trotsky’s side. More than 100 years after van Heijenoort was born in 1912, capitalism is in crisis again. But people of his caliber aren’t dedicating their lives to overthrow it.

When Jean heeded the call of revolutionary socialism, he was one of millions who were certain that capitalism was on its last legs. Apart from the evidence staring them in the face, a large body of serious theorizing said the system’s collapse was inevitable. The Soviet Union seemed to offer a plausible alternative. Plausible under some conditions. For Trotsky and his followers in the 1930s, the conditions included ending Stalin’s dictatorship, halting the liquidation of the revolutionary class of 1917, as well as the murderous forced collectivization of agriculture.

Jean eventually realized that the supposedly inevitable proleterian revolution wasn’t, in fact, destined to happen. He also came to accept that Trotsky, among others, laid the foundations of Soviet totalitarianism. In the 1950s, though he had renounced political activity, he signed on to help the U.S. government prosecute one of the most sinister of the corps of Soviet agents deployed against Trotsky and his circle. Jean and others like him wound up on the U.S. side in the Cold War in large part because the other side had been trying to kill them.

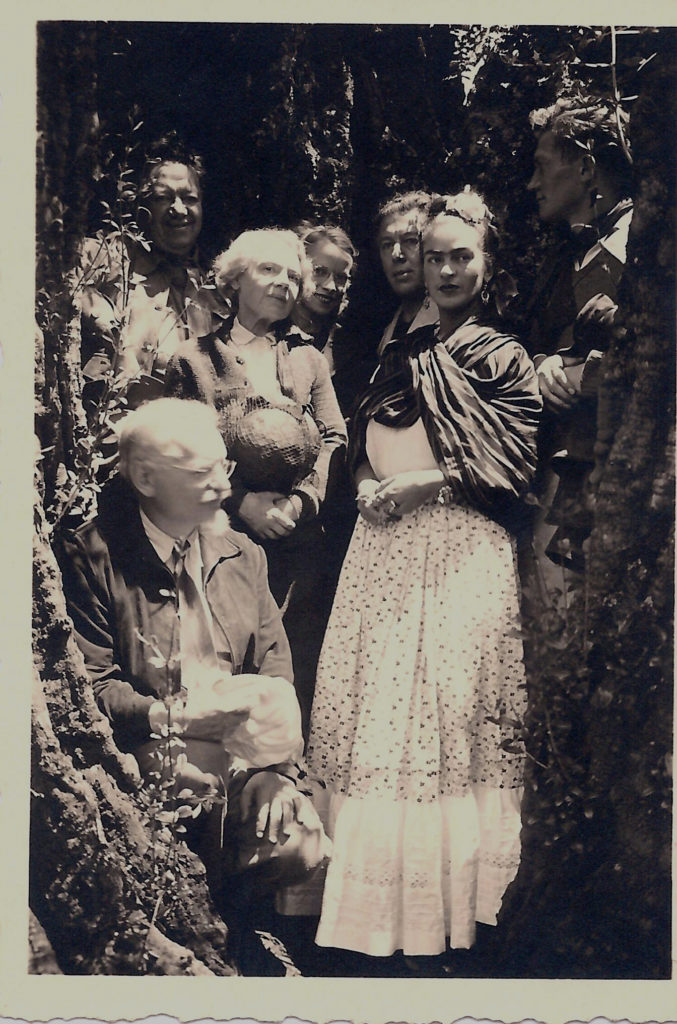

This dimension of Cold War history is pretty much forgotten. Periodic bouts of nostalgia about the 1940s and ‘50s still typically focus on targets of anti-Communist investigation – celebrating and occasionally condemning the work of pro-Soviet artists and entertainers (Jean shared his centennial with one of them, Woody Guthrie). Jean himself appeared as a major figure, “Van,” – as Trotsky and many others did call him – in The Lacuna, a novel by Barbara Kingsolver. The book’s plot unfolds partly in Trotsky’s final refuge in Mexico – a setting portrayed much more accurately in Hayden Herrera’s definitive biography of Frida Kahlo, for which Jean was a major source (the film version includes Jean as a character, albeit briefly). Kingsolver, for her part, foolishly and ignorantly conflates the experiences of ex-Trotskyists and ex-Stalinists during the McCarthy years.

Members of those groups didn’t, in fact, have any more in common during that period than they’d had in the years leading up to it. By 1948, Jean wrote in his 1978 memoir “the full extent of Stalin’s universe of concentration camps became known at least to those who did not wish to close their eyes or stop their ears.”

Former Vice President and failed presidential candidate Henry A. Wallace was in the latter camp. He’s resurrected by filmmaker Oliver Stone and history professor Peter Kuznick. In a TV documentary series and book they depict the politician as the man who could have ushered in an era of prosperity and international good-fellowship.

Wallace made his presidential bid as candidate of the Progressive Party, a wholly owned and operated subsidiary of the Communist Party. Perfect for the part, Wallace had visited Siberia in 1944 without, apparently, realizing that its population consisted of labor camp prisoners and their guards. “Compulsion everywhere appears to him as the spontaneous will of the people,” Dwight Macdonald wrote of Wallace’s rhapsodic account. In which he likened Siberia’s population to 19th-century American homesteaders. (By 1952, historian Sean Wilentz notes, Wallace reversed course and denounced Soviet communism as “utterly evil”).

In the 1930s, when Wallace was climbing the rungs of the U.S. political system, Jean, a friend and comrade of my parents since those years, was serving as Trotsky’s executive assistant – translator, bodyguard and negotiator with foreign governments. He had been recruited for Trotsky’s staff from the French Trotskyist movement at age 20,in part because he had taught himself Russian.

The job was not for the faint-hearted. Jean worked closely with three men who would be murdered or “disappeared” by Soviet agents: Erwin Wolf,kidnapped by NKVD operatives in Spain and never seen again; Rudolf Klement and Leon Sedov, Trotsky’s son, who were killed in Paris. Within the USSR, about 1 million people accurately or not accused of Trotskyism were executed, in addition, of course, to the millions of peasants who were killed or died of starvation in the forced collectivization of agriculture. All in all, Stalin’s victims number at least 15 million, historian Robert Conquest has calculated.

Trotsky himself met his end in 1940, in Coyoacán, Mexico. Ramón Mercader, a Soviet agent born in Barcelona, used a cut-down mountaineering axe, driving its broad end into Trotsky’s brain. Mercader had infiltrated French Trotskyist circles and then the Trotsky household by seducing a young American Trotskyist. Her sister had done secretarial work for Trotsky in Mexico, which helped give the unwitting Soviet tool entrée to the exile’s household – entrée to the assassin as well. The woman had been spotted as a prospect for Mercader’s attentions by an American communist who had infiltrated the U.S. anti-Stalinist left.

Jean had left Trotsky’s household amicably a few months before the exiled revolutionary was killed. But he stayed on the Soviet target list. “By what route does VAN intend to travel to FRANCE?,” the NKVD’s Moscow Center demanded to know near the end of World War II in April, 1945. The message was decoded by the Venona project, the decryption operation on Soviet spy message traffic then run by the U.S. Army – and which also led to the discovery of the Soviet spy operation at Los Alamos. In the encrypted message about Jean, a spy code-named KANT had reported that Van was planning to return to his homeland from his new base in New York to lead the French Trotskyist movement. “What is the extent of KANT’s knowledge about the plan for VAN’s trip?,” continued the Moscow message continued. “[G]et KANT to take up this question in real earnest so that he knows all the details of the preperation for the trip.”

These, of course, were not idle inquiries. KANT was Mark Zborowski, the main NKVD spy at the heart of the Trotskyist movement. He was unmasked as Soviet spook in the early 1950s. The Ukraine-born Zborowski had joined the Trotskyist Party in Paris in the 1930s, on assignment from the NKVD. He gained the trust of the doomed Sedov and played a key role in his murder. Zborowski fled to the United States in 1941. By the time he was identified as a Soviet agent he had become an anthropologist in the U.S. under the patronage of Margaret Mead.

Jean, who had been questioned by government agents with some regularity since arriving in the United States in 1939, became a source for FBI agents as they tried to build a case against Zborowski. “He is completely frank and open with the agents interviewing him and at one point volunteered to assist the government by voluntarily going to Harvard University to review Trotsky’s documents in order to garner additional facts,” the FBI’s New York office reported in 1957, in one of a series of documents I obtained under the Freedom of Information Act (cops being cops, the FBI held Jean’s application for U.S. citizenship over him).

Trotsky had sold his archives to Harvard, and Jean, who had had negotiated the transaction, organized the papers for the transfer and knew them better than anyone. The FBI eventually assigned agents to comb through the files with Jean in August, 1958. Details of what they found were blacked out in the memo I obtained. But the FBI documents overall make clear that the focus was on a pair of Soviet agents, one of whom turned up in New York in the 1940s as an espionage contact of Zborowski. Jean eventually testified as a government witness when Zborowski went to trial. After winning one appeal, the anthropologist-agent was convicted of having lied to a Senate subcommittee about spying in the U.S. (after serving less than two years in prison, he relaunched himself as a medical anthropologist in San Francisco, where he died in 1990 – his San Francisco Chronicle obituary written by ex-Trotskyist Stephen Schwartz, who had known Jean).

By the time he appeared in court, Jean had earned a doctorate in mathematics from New York University, eventually writing and editing seminal works in the discipline of mathematical logic. He had two children (and now grandchildren and great-grandchildren) on two continents, in France a son of the same name, a biochemist; and in the U.S., a daughter, Laure, a lawyer in Albuquerque, NM.

In a stroke of fate that a novelist might hesitate to invent, Jean was killed in Mexico City in 1986. His wife, his fourth, shot him to death, then killed herself. She was the daughter of Trotsky’s Mexican lawyer.

Jean at the time was still going through the archives of his earlier years. The memoir that fortunately he had already published depicts a tiny, hunted band, unsure of its existence from one moment to the next. Trotsky’s failings on a human level come into view, as well as the insights that explain the allegiance of people like Jean.

“In June or July of 1939, Trotsky asked me to do research in Mexico City’s National Library and try to find some texts on the 16th century wars of religion and on the end of the Roman Empire. According to him, these two epochs of historical fracture were the ones to compare with ours. I can still see the scene in his study as he stood near me. I made some objections, mentioning the atrocities of the wars of religions, in which people were hurled down from towers onto the spears of soldiers waiting below. He gave me a look of rare sadness and said, ‘You shall see.’ We have seen.”

And we’re still seeing.