One hundred years ago, my grandfathers Ilya Eduardovitch Katel and Boris Isaakovitch Gessen tried to make sense of the new world emerging from the ashes of World War I and the flames of the Bolshevik Revolution – events that had upended their lives.

The two of them were old-fashioned liberals. At the time, liberalism – in the European sense: Capitalism plus political pluralism and civil liberties seemed to have a fighting chance.

Seemed, at least, to political amateurs like Ilya and Boris, who thought it could win the day even in their Russian homeland, then torn by civil war. They didn’t understand that the soon-to-be winners, the Bolsheviks, weren’t interested in conventional notions of progress. The Bolsheviks saw themselves as the vanguard of a world revolution. Ilya and Boris didn’t understand that vision, but millions embraced it. Later on, millions also exulted in a campaign to exterminate “race enemies.” Less than halfway through the 20th century, Ilya and Boris surely learned that unimaginable doesn’t mean impossible.

The lesson seems not to have endured. Until a few years ago, the idea of an American president siding with a Russian dictator was unimaginable. Ilya, who revered the United States as a model and guide, would have been stunned. Boris, who got a closeup view of how the Kremlin operated, would have been horrified.

***

Nevertheless, Gessen (I’ve kept the Russian version of his last name, which became Hessen in the West) began in politics by donating to Lenin’s Bolsheviks. Having lived earlier in Kishinev, now Chișinău in the Republic of Moldova, where he survived the infamous 1903 pogrom, Boris had become a wealthy St. Petersburg businessman by the time he contributed to the Bolsheviks, who were years away from seizing power. By the time they did, in 1917, Boris had changed his mind. Days after the Bolshevik coup, he fled St. Petersburg with his family – my mother, born only weeks earlier, was the newest member – only days after the coup. He set them up on Finland’s Karelia Peninsula.

There, in 1919, he joined the civilian leadership of one of the anti-Soviet “White” armies, commanded by Nikolai Yudenich, that was trying to topple the fledgling Soviet government.

Within a year or so, Boris and his brother and business partner, Julius, realized that the Yudenich forces were Jew-hating bandits. This was something widely known by the time the brothers joined the cause, so why did they? My best guess is that they acted from political expediency. Boris’ heart was with Alexander Kerensky, the liberal who led the first post-Czarist government, the one that the Bolsheviks toppled.

Kerensky couldn’t hold on to power, and the Whites were a bad bet all around. But Boris, not insightful in choosing allies, was ahead of his time in understanding the power of cinema, which was still in its infancy. He devised and produced a film designed to support the anti-Soviet war – Under the Yoke of Bolshevism. According to its script summary, the 1919 film was a melodrama as subtle as its title. Its main villain is a commissar who sends patriotic young Russians to the firing squad. The hero escapes to Finland. There, the official script outline says, “He swears an oath to take revenge on the enemies of Russia, his ravaged native country.”

Boris’ family had forgotten about or never known about his brief movie career, which was rediscovered by Ben Hellman, a Russian literature scholar at the University of Helsinki. He unearthed a wealth of documentation, though not the film itself, which vanished long ago. Hellman’s research added to a portrait of Boris by Valeri Gessen, a distant cousin of mine in Moscow. Valery Bazarov, then of HIAS (the longtime Jewish refugee-aid organization), and a brilliant researcher and writer, put us in touch.

Boris had a stake in opposing the Bolshevik takeover. He had made himself a rich man in late-czarist Russia, founding an insurance company and a steamship freight line on the Volga. The jewel in his crown was KAMVO, a company he started in 1913 to ship goods from London to Persia via Russia, using the firm’s own ships, barges, warehouses, cranes, and repair shops. The petroleum age had dawned in Persia, but the British owned the country’s nascent oil industry. Boris saw a promising future in transporting the industry’s supplies, and bought Anglo-Persian Oil Company bonds. “We are resolute advocates of private initiative in the business of transportation and the establishment of insurance business,” he wrote in a seven-page memorandum at roughly the same time as his movie project. “Now, when all the means of transportation and its use are in the hands of state power, transportation should be at the peak of perfection; yet we have an absolute failure, a lifeless corpse.”

Having misjudged the Whites, as well as the Bolsheviks’ tenacity, Boris didn’t let his good will color his judgement when the Soviets invited Boris and his brother back to Russia to share their expertise. Brother Julius wasn’t so skeptical. He trusted the words – summed up by Valeri Gessen – of an official of the Peoples’ Commissariat for Transport: “…[T]hat his activities as an enemy of the Bolshevik regime were well known, but that F.E. Dzerzhinsky trusts him.” This was Felix Dzerzhinsky, who founded the Cheka, first of the Soviet and post-Soviet spy agencies. The invitation was a trap, of course. After traveling to Moscow, Julius was arrested in 1929 (Dzerzhinsky, whatever his word would have been worth, had died by then). Interrogated for months, Julius was sentenced to death as a foreign agent. Execution was postponed so that Julius could be charged in a new case, but he died in prison before another trial could be mounted.

***

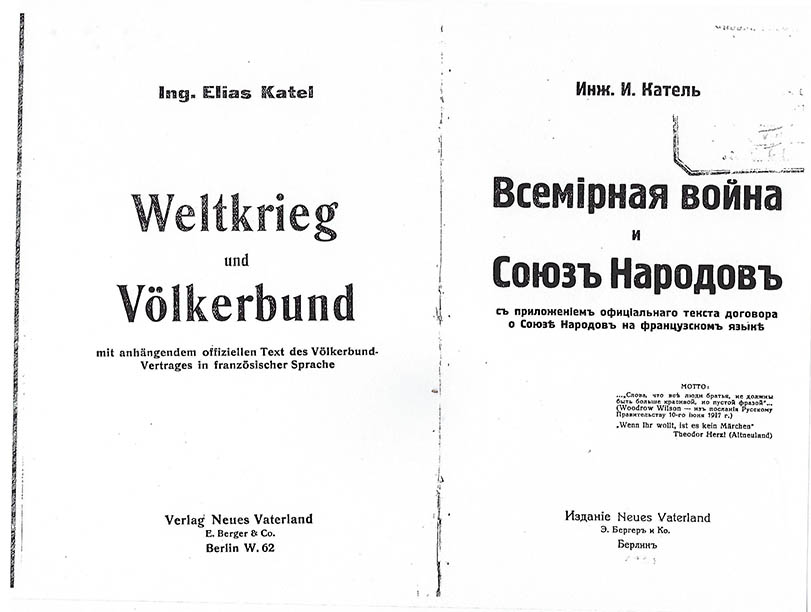

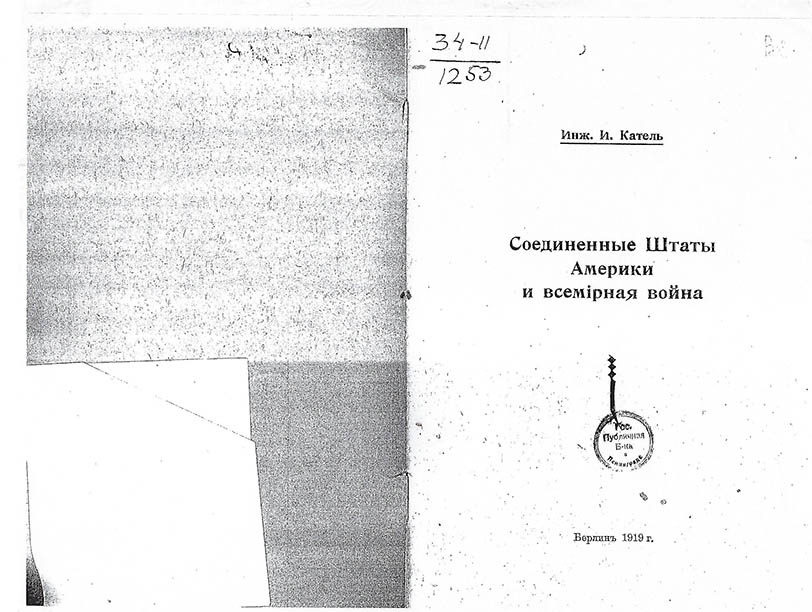

While Boris was producing anti-Bolshevik propaganda, Ilya – my father’s father – was in Sweden. He had left Kharkov (now Kharkiv), Ukraine, when his marriage to my grandmother fell apart. World War I was raging and my father and his sister never forgave Ilya for deserting his wife and two small children in wartime. With the war over, Ilya wrote a short book, published in 1919 in Berlin, which was already filling up with Russian refugees, arguing that the United States and President Woodrow Wilson would lay the foundations of a just and peaceful postwar world. The President, Ilya wrote, “was a definite foe of imperialism and interest-driven politics and stood up for every nation’s right to live independently and under a regime in which the nation feels free.”

It was a nice thought. Ilya almost certainly knew nothing of Wilson’s deep-seated racism, nor of the anti-black massacres in Washington DC and other U.S. cities, that peaked in 1919. And, of course, he knew nothing of the ferocious isolationism that would doom Wilson’s internationalist vision. All this might have tempered his admiration for the United States, where he wouldn’t set foot until two decades later.

Ilya’s optimism was born of what seemed to be the defeat of German militarism and the dawn of an age of self-determination for peoples including the Armenians and the Jews. Kharkiv, where Ilya had lived, was a Zionist center and the point of origin for the first modern Zionist pioneers to travel to Palestine. Ilya seems to have absorbed some of their spirit. One of the epigraphs to his book was the famous line by Theodore Herzl, the founding father of modern Zionism: If you will it, it is no dream. Referring to a Zionist delegation’s 1919 proposal for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, Katel wrote that a favorable reception for the idea at one of the postwar peace conferences “signifies the actual start of a new epoch in world history, for the new spirit has so deeply touched the people who are most persecuted and most deprived of rights.”

As for the new Soviet rulers, Ilya’s postwar cheerfulness extended even to them. “There are a number of signs pointing to the fact that the Bolshevik rulers finally are beginning to understand that their regime is bound to be bankrupt, so let’s hope that they have courage and sanity to lay down their weapons before the eternal principles of democracy, which benefit all.”

He dedicated a companion volume of commentary on the League of Nations treaty, not only to the “Russian intelligentsia but also to every Russian citizen who pursues the triumph of justice and peace on earth.” After all, “in no other people does the feeling of international solidarity live so deep as in the Russian one.”

Nevertheless, Ilya seems to have abandoned his hopes for Russia at some point, as well as his sideline in political analysis. A reconciliation with my grandmother failed – after she exited the new Soviet state for Berlin – and he emigrated to Paris, where he started an engineering firm that became successful enough for him to have a big American car and a chauffeur. From then on, he limited his writing to engineering topics, such as “How to Combat Industrial Noise,” published by the French Society of Civil Engineers.

Still, Ilya’s earlier faith in the United States eventually proved valid. When World War II broke out, Ilya made his way to Marseille – then under Vichy control – and ultimately found shelter in the United States thanks to HIAS, the refugee-aid organization where my parents then worked. HIAS was headed in France by yet another liberal Russian Jewish refugee, Wladimir Schach, whose son married my mother’s older sister.

The family connections don’t end there. Schach, a largely unsung hero who ran an operation that saved thousands from the Nazis, had been a lawyer for Boris’ companies back in prerevolutionary Russia.

Ilya went back to France after the war, and died there in 1972. My father, who saw Ilya only a few times in the United States, never took me or my brother to meet him, so deep was my father’s contempt. I could have looked Ilya up after my father died in 1965, but I never gave it a thought. I’ve only seen one photograph of Ilya, and now I can’t find it.

But even though estranged from Ilya, my father in effect acted on Ilya’s faith in the United States. Though he and my mother had been dissident communists, Trotskyists, in the 1930s, once settled in the United States, they became U.S. patriots and democratic socialists – the kind who opposed Soviet totalitarianism because they were socialists.

***

And how did things turn out for Boris? He established himself in Warsaw in the ‘20s, while his family was in Paris. His marriage to my grandmother wasn’t much happier than my other grandparents’ union. As war became more and more likely, he apparently didn’t attempt to flee west. But his survivor’s instinct was strong enough to keep him alive during World War II. My mother heard after the war that he had hidden with peasants in the countryside. His survival must have taken considerable skill and luck. (The remaining Gessen brother, Alexander, who had run the Riga, Latvia branch of the family business, had headed west after World War I and eventually wound up with his daughter and son-in-law in Forest Hills, Queens).

Boris had experienced in Kishinev one of the founding events of 20th century antisemitism, then survived its apotheosis. And after knowing the Bolsheviks before they seized power, and then fleeing them, he ended up in what became a Soviet vassal state. Did the “state security organs” ignore him, or overlook him? I don’t know. All that I do know is that his last business venture was selling jars of mushrooms that he pickled in a bathtub.

And those Persian oil bonds? At least as late as 1937, Boris was reporting that he expected “good news from Persia.” I don’t know how long his hope lived on. As it happens, the bonds were stored in an attic somewhere where rats made a meal of them.

The 20th century wasn’t always kind to optimists. But Boris, a risk-taking bon vivant, and Ilya, sober-minded and cautious, both tended to look on the bright side. In hindsight, their judgements were sometimes faulty. But their optimism probably helped keep them alive.

© Peter Katel. All Rights Reserved.

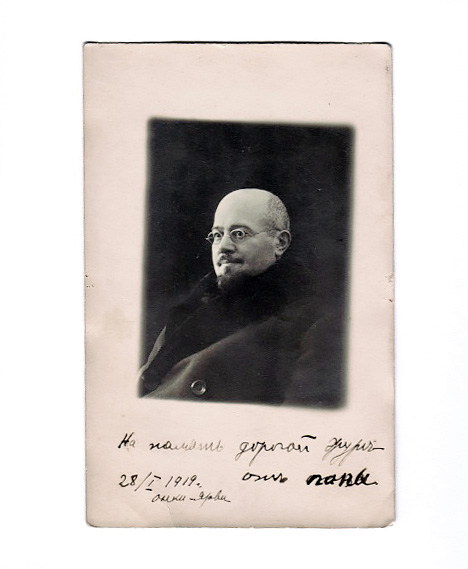

Featured image at top of post: Boris in 1919. It is inscribed to my aunt Yevgenia (Zhura) “Dear Zhura, a keepsake from Daddy.” Photographer unknown.