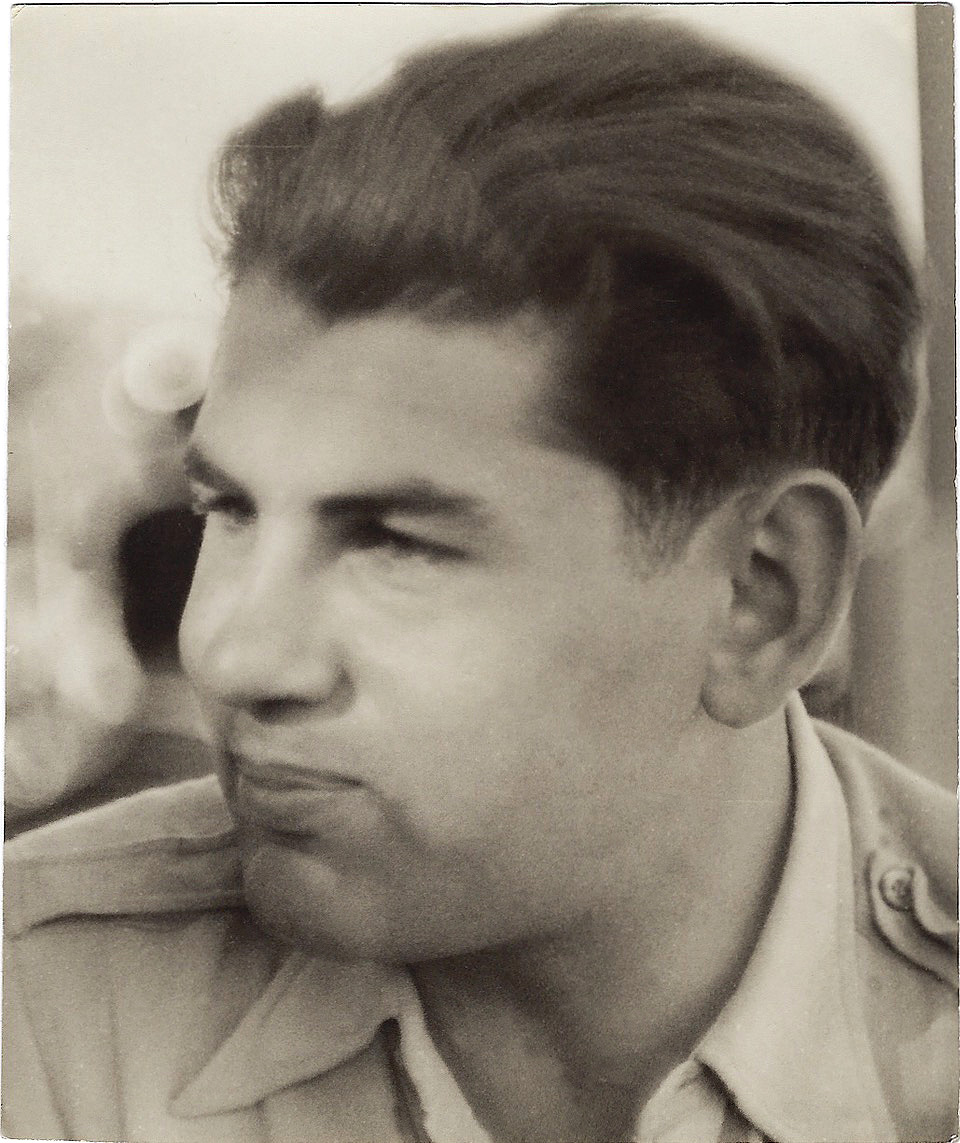

Who Was Jacques Katel?

Article published in 2015

Jacques Katel, my father, died in New York 50 years ago, on May 7, 1965, nine days before his 49th birthday. Next year will mark 100 years since he was born during World War I in eastern Ukraine – a battlefield then and a battlefield now. New York was his last stop in a series of moves, starting with Moscow in 1920 or 1921, where his first memory was standing on a bread line.

The Katels – Jacques (born Yakov Ilyich), his sister Valentina and their mother, Amalia Kopp, a pediatrician – had gone to Moscow to try to get exit visas to leave the newly formed Soviet Union. Before then, the Katels hung on in Kharkiv, an industrial city on the Russian border ravaged by the civil war that followed the Bolshevik revolution. At one point, when the family wasn’t home, a bullet fired into their house hit the wall above his crib.

After getting their visas in 1922, they headed west to Berlin, a refuge for thousands of Russian refugees. Many like the Katels, were Jews.

Familiar with the mobilizing force of Jew-hatred, they saw it in action again as the Nazis were rising to power. Hitler’s party had foes, but one of the biggest, the powerful German Communist Party, followed Stalin’s order to make the Social Democrats – not the Nazis – the number-one enemy. In this usually ignored chapter of the World War II origin story, one of the few to see disaster ahead was exiled dissident communist Leon Trotsky. One day on the street, a Trotskyist militant handed Yakov a copy of a pamphlet by Trotsky denouncing Stalin’s policy as paving the way for Hitler. This made sense to Yakov, then 16 years old, and set him on the course that defined his remaining 33 years.

At the same time, back in the Katels’ native Ukraine, one of the century’s worst atrocities was under way. An estimated 3.3 million people died of starvation, as the state seized food and crops, part of Stalin’s forced collectivization of agriculture. Jacques would not have been surprised that the pro-Russian forces now ruling parts of eastern Ukraine are trying to whitewash the forced collectivization. The Stalinist rewriting of history was one of his choice themes. “For over a quarter of a century,” he wrote a few months before he died, “those who dared mention the existence of slave labor camps in the Soviet Union, who dared question the truthfulness of the confessions, who had likened the Moscow trials to the Inquisition, were promptly branded as liars, reactionaries, fascists, war-mongers.”

For Jacques and others from the now-vanished civilization of the old Left, the USSR was the reactionary force – an especially dangerous one because it harnessed humane ideals in service of a murderously oppressive system. He was planning to write a book about the vast purges of the 1930s, to appear on the the Bolshevik Revolution’s 50th anniversary. But the book died with him, when a aneurysm burst in his brain, probably speeded along by a two-pack-a-day Marlboro habit. I don’t believe he imagined the Soviet Union collapsing before the century ended, but he would not have been surprised to see a graduate of the Soviet spy services sitting in the Kremlin.

Trotsky’s desperate call for the entire Left to unite against Hitler failed, of course. Once Hitler had become chancellor, a gymnasium schoolmate of Yakov showed up at school in his brownshirt uniform. Jacques, a one-time Zionist boy scout who had absorbed teachings of Jewish self-defense, beat him up. Then he beat up a Latin teacher who called him a “Jew pig.” I cannot confirm these accounts, but I believe them, in part because Jacques only spoke of them once. The school director, a decent guy, warned Amalia that the Katels should get out of Germany. This confirmed her own instinct. The family again headed west.

In Paris, Yakov– not in this order – passed the baccaleaureate exam, entered university, graduated as a lawyer, joined a Trotskyist organization, and met my mother, Helen Hessen, another Russian Jewish refugee attracted to Trotskyism. He also became a French citizen, through his father, an engineer who had left the family back in Ukraine and founded a successful soundproofing company in France.

Yakov became Jacques, the name he used for the rest of his life.

In France, he acquired a taste for French food and wine, and a deep appreciation for the rigor, passion and competitive spirit with which the French argue about important matters. Verbally deft, with a prodigious memory and a booming voice, he was a born debater in any case – another reason he was repelled by Moscow-brand communism, which prized unblinking obedience to the party line.

In August, 1939, after the signing of the Stalin-Hitler Pact, the line went soft on Naziism again. (As I was writing this, Vladimir V. Putin defended the pact). When war broke out one week later, Jacques was called up. His file stamped Presumé Révolutionnaire, he was assigned to an infantry regiment deployed near Sedan. The German Army made a major breakthrough there during the May, 1940 invasion of France, overrunning the defenders (overall, 124,000 French troops were killed during the six-week campaign – more than double the number of American soldiers killed during 10 years of war in Vietnam). Jacques spoke to me only once of the German attack, telling of riding in the cab of a truck that dodged a Luftwaffe plane’s strafing run. Jacques and a handful of comrades headed south. Eventually, Jacques and Helen met up in southern France, then ruled by the Vichy collaborationist government, and set out for Marseille.

That Mediterranean port city was the real Casablanca – teeming with desperate refugees searching for exit visas, Vichy police, early Resistance cells, visiting Nazi officials, smugglers, black-marketeers, good-hearted American rescuers, spies. Jacques loved it, said my mother, who was less enchanted. Jacques joined HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, which had reestablished itself in Marseille under the name HICEM. Assigned to Camp des Milles, one of the Vichy detention camps for foreigners, most of them Jews, he helped prisoners write visa applications. Helen did visa work in Marseille. By 1942, they managed to get U.S. visas for themselves and for Amalia.

Upon reaching the United States, Jacques found work at the Office of War Information, which eventually sent him to London to work at OWI’s French-language American Broadcasting Service in Europe. By then, he had abandoned Marxism-Leninism for democratic socialism, and learned English. After the war, Jacques and Helen went to Germany, attached to the U.S. Army, to help ex-concentration camp prisoners get U.S. visas.

In 1948, the Katels returned to New York, where Jacques joined Agence France-Presse as a correspondent at the newly formed United Nations.

A few years later, he became UN representative for the World Veterans Federation. Then, in 1960, he took his last job, at a startup monthly, Atlas, the Magazine of the World Press. His main interest all this time was the Soviet Union – its repression of its own people, its falsification of history, and its spreading power in what people then called the Third World.

Jacques and Helen had become American citizens in 1949, a few weeks before I was born. They lied on their applications, denying they had had been members of a communist party. Well, sort of lied. They had belonged to the Ligue comuniste de France and the Parti ouvrier internationaliste, tiny Trotskyist outfits targeted for sabotage and murder by the Communist machine run from Moscow. “Officially” Communist was what the immigration form meant by communist, my parents decided, correctly. But they were always careful to say that they’d been part of the Trotskyist “movement,” not party.

You might think that that experience would have made Jacques take the common view of the McCarthy period as a time of inquisitorial terror. You would be wrong. McCarthy was a “pipsqueak,” he said, who aided the Communists by using the label for anyone left of the Republican Party. But McCarthyism didn’t measure up as state terror for Jacques, whose friends included some widows and children of men murdered on Soviet orders in France and Spain during the 1930s and ‘40s.

Besides, Jacques lacked sympathy for Stalinists and fellow-travelers hauled before congressional committees. The one case he knew intimately hardened his opinion. Mark Zborowski, a Senate Internal Affairs Committee target of the early ‘50s, was a former Trotskyist comrade in Paris. Jacques had helped him get a U.S. visa and land his first U.S. job. Zborowski turned out to be a Soviet mole who had played the key role in the murder of Trotsky’s son, and at least one other killing. In the States, Zborowski had turned himself into a well-known American anthropologist. Once he was unmasked, his mentor, Margaret Mead, defended him as – of all things – a victim of human sacrifice; she helped him settle into a comfortable professional life in San Francisco after he served a brief sentence for perjury.

The real American political repression of the ‘50s and ‘60s was going on in the South.

Jacques admired the raw physical courage and militant spirit of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. And he was fascinated by Malcolm X, who reminded him of 19th-century Ukrainian Zionists and socialists who organized self-defense squads. Many American Jews, ex-Trotskyists among them, didn’t share that view. A few weeks before he died, Jacques told me that, at a party, he’d gotten into a furious argument on the matter with political journalist Theodore H. White, who had been a youthful Zionist in Boston. But Jacques carried the imprint of his early years. American Jews, he said, knew nothing of life as a minority in mortal danger. As someone who did, he understood why many Holocaust survivors didn’t want to live anywhere but a Jewish state. But he rejected idealized views of Israel and saw trouble ahead for the new country in its treatment of Palestinian Arabs.

Some aspects of the American scene eluded Jacques. Having arrived when he did, it was plain to him that Franklin D. Roosevelt saved capitalism. Plain to anyone with eyes in his head, or so he thought. But less than a year before he died, he was stunned to meet a Wall Street banker who railed that the New Deal had ruined the economy. Jacques couldn’t believe what he was hearing. I wonder if he would have believed how popular the Wall Streeter’s argument would become.

I don’t have to wonder how he would feel in a time filled with wars, tyrants, refugees and economic disaster. Fifty years after he died, Jacques would feel right at home in today’s world.

Read some of Jacques Katel’s published works here.